We Need To Talk About Kevin

In 2011, Scottish filmmaker Lynne Ramsay surprised with a disturbing, tragic and controversial story. A story in which the myths about motherhood are blurred, in which the innateness of evil is questioned and that will shake more than one viewer. The film is none other than We have to talk about Kevin , the adaptation of the novel by Lionel Shriver.

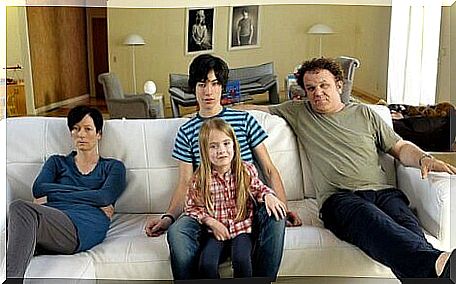

Starring an incredible Tilda Swinton as Eva and an awkward Ezra Miller as Kevin, the film immerses us in a fragmented narrative, with a fairly predictable, but effective intrigue.

Motherhood is often idealized in the movies; the role of mothers is elevated to unsuspected heights. However, We have to talk about Kevin presents us with a different vision, a nightmare, the worst for a mother: facing the evil of her son.

Eva, a woman who perhaps did not consider motherhood at first, will have to deal with a difficult situation. She will be forced to try to understand and help a son who is conflictive from his first steps in the world and who will end up unleashing the worst of tragedies. We have to talk about Kevin is a film that addresses a taboo subject, that explores the worst of horrors.

Blood, entrails, entrails

From the beginning of the film, we observe an omnipresent image of the color red. A color that we inevitably link to the tragic, to blood, to the viscera. Eva finds herself bathed in red, ecstatic over fun at a Spanish party, the Tomatina de Buñol. Young and carefree, the protagonist is carried away by the moment, by that bath in tomatoes that seem to anticipate what will later be blood.

It will not cost the viewer too much to find the references to red, a color that acts as a common thread throughout the film adopting multiple forms : tomato in different versions (Tomatina, ketchup), red paint or even jam, to end up being what we all feared: blood.

We are not facing a red that evokes passion, but viscera. In this sense, gestures and small details take on special relevance. We observe various close-ups of hands, gnawed nails and chewing mouths. These are unpleasant, uncomfortable shots, despite showing everyday actions.

They are nothing more than games with our mind that associates the scenes with the perverse. Without going any further, we see in a food certain similarities with the eye that the protagonist’s sister has lost or, as we have anticipated, we find in a simple jam sandwich connotations that evoke the catastrophe. Somehow, through these images, we anticipate the tragedy, as the viewer is in a constant state of alert.

From his birth and childhood, Kevin shows signs of being somewhat strange, distant, and manipulative. Therefore, as viewers, we expect to see something atrocious from you, we are on the lookout and, in a way, prepared for what is to come. But Ramsay directs our gaze correctly, evokes these sensations without actually showing the perversion.

Likewise, red, in addition to making us suppose the tragedy, has an even deeper connection: with childbirth. The blood, the viscera and the entrails, that irrevocable union between mother and child that, although they do not understand each other, will keep them together forever.

And all this enlivened by music capable of giving life to emotions, but also of contrasting with what is seen on the screen. Thus, for example, we have the jovial Everyday of Buddy Holly accompanying the heartbreaking face of Tilda Swinton.

We need to talk about Kevin : destroying stereotypes

As we have anticipated, We have to talk about Kevin distancing himself enormously from the stereotypes of motherhood and, even, from the roles of a couple.

Eva does not display an excessive maternal instinct, but her partner, played by John C. Reilly, looks enthusiastic. However, that enthusiasm will eventually blind the parent who is unable to see or accept his child’s mistakes. While she tries to find a solution or explanation for the sociopathy that the child seems to have, the father prefers to look the other way.

In fact, the relationship between the parents is really interesting. It is true that the father plays a very residual role in the film, he hardly appears and his scenes are, essentially, happy.

The worst part always seems linked to Eva. And while this may be seen as a mere focus of the film, it is actually revealing. In other words, the fact that the father figure barely acquires relevance in the film only means that the same happens in the life of the family.

Thus, we have, on the one hand, a father who allows himself to be manipulated by his son, who prefers to live the illusion of having a wonderful child and a perfect family; on the other, to a mother who may not have the greatest maternal instinct in the world at first, but who cares enormously about her son’s attitude. A mother who sees that Kevin is in trouble, who manipulates at will, and who shows signs of violence.

The viewer perceives, in a way, a single mother, the figure of the father is irrelevant, although it benefits Kevin. By dosing the story through flashbacks , we understand that society today blames Eva for something Kevin did.

The viewer will soon wonder why they blame her, if she, as a mother, really has any responsibility for her son’s actions or if, in some way, she tried to cover it up.

The doubt remains until the end and, in my opinion, that is what keeps us glued to the screen. Regardless of what Kevin did – since it is something that we can easily imagine and perhaps there the film limps – the intrigue lies in the guilt or not of his mother.

A predictable intrigue, a mystery for which the viewer expects an answer: was there a before and after? Was Kevin always mean? Is it the lack of affection or the prozac? We do not know and, hence, Ramsay decides to split his story in order to maintain the uncertainty.

The interesting thing is that, beyond Kevin, the point of view is fully focused on his mother, on her present and past events, on how she has coped with the situation and on the internal conflict that is unleashed in her: every mother loves her your child, but you can reject it at the same time.

Society will point to his mother as guilty, something that awakens in us a certain discomfort, because it is done more frequently than we think and we try to find a reason for the evil when, perhaps, it was innate.

Horror without demons

Wickedness in childhood has often been justified in the movies through demonic experiences. It is disturbing to see a child full of evil, but also uncomfortable.

It is likely that, for this reason, many filmmakers have decided to give it a supernatural component; that is to say, to justify the badness in the childhood by means of the fantasy. Many “seeds of the devil” have permeated our cinema, but We Gotta Talk about Kevin completely avoids the fantasy element.

Little Kevin’s wickedness is on a par with the diabolical children of the horror genre; however, there is nothing in him that seems to indicate that he was begotten by the devil himself. Is your family guilty? Are we looking for the culprits outside or inside the individual?

From the initial sociopathy to later horror, Kevin is shown as a listless, manipulative and ruthless being that reminds us of episodes far from the demons, but very close to reality like the Columbine massacre. M

asacre in which the guilty were found in the doctors who administered antidepressants and in a society that tolerates weapons when, surely, the keys were found in the diaries of the architects and between several factors.

Risky and heartbreaking, We Gotta Talk About Kevin is a necessary film that raises a problem that seems to remain taboo. The horror beyond demons and motherhood beyond the idyllic go hand in hand in a film that continues to preserve its essence, that does not age and that takes us down a bitter path full of questions.