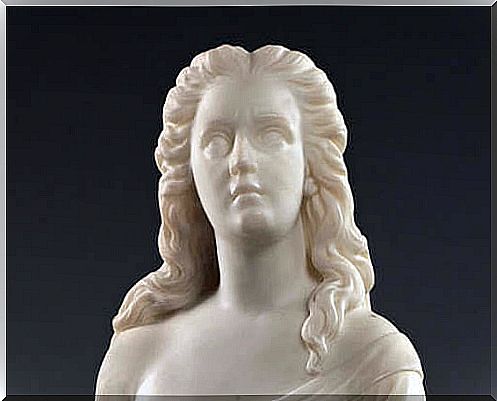

Edmonia Lewis, Pioneer In Sculpting Her Destiny

Mary Edmonia Lewis was an American sculptor who worked most of her career in Rome, Italy. Born free in New York, Edmonia Lewis was the first woman of African American descent to achieve international fame.

In addition, she was the first African American to achieve recognition as a sculptor in the world of fine arts.

Many North American artists of the s. XIX and XX enjoyed fame in their own country. However, Edmonia Lewis is one of the few exceptions. Discover his life and work, how he managed to overcome the obstacles that society imposed on him, break the molds and, against all odds, acquire worldwide recognition.

Edmonia Lewis childhood and youth

Edmonia Lewis was born a free black woman around 1844 in Greenbush, New York. He had a brother who, as an adult, would be financially successful thanks to gold mining.

Little Edmonia was the daughter of a black man servant to a knight; while his mother, also black, had Ojibwa and African ancestry. The Ojibwa are one of the largest native peoples in North America alongside the Cherokee and Navajo.

Edmonia was orphaned around the age of ten. As she later claimed, she was raised by some Ojibwa relatives near Niagara Falls.

Mary Edmonia Lewis had little training, however, with the support of a successful older brother, she attended Oberlin College in Ohio. There she studied from 1860 to 1863 emerging as a talented artist.

At the time, the abolitionist movement was active on the Oberlin campus and would have a major impact on Edmona’s later artistic career.

The price of success

The young woman had to overcome numerous obstacles to become a respected artist. At Oberlin College, she was falsely accused of attempting to poison two white classmates, as a result, she was captured and beaten by a white mob. Lewis recovered from the attack and subsequently escaped to Boston after the charges against him were dropped.

In Boston, Lewis befriended the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison and the sculptor Edward A. Brackett. It was Brackett who taught Lewis’s sculpture and helped her launch her own studio.

In the early 1860s, Lewis began to receive certain accolades for his work, carving out a niche for himself in the art world. His clay and plaster medallions, depicting Garrison, John Brown and other abolitionist leaders, opened a small door for him to moderate commercial success.

In 1864, Lewis created a bust of Colonel Robert Shaw, a Civil War hero who had died commanding the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. Thanks to this work, he would obtain his first considerable commercial success.

The money he earned from the sale of copies of the bust allowed him to move to Rome. Why move to the Italian city? At that time, Rome had become home to a number of American artists who had been expatriates, including several women who had come to the city in search of an opportunity.

Lewis and his life in Rome

In Italy, Lewis continued to work as an artist. His work tackled, mainly, a theme linked to his Afro-American cultural heritage and, secondarily, to his religion, Catholicism.

One of his most applauded works was Free Forever (1867), a sculpture depicting a black man and woman emerging from the bonds of slavery. Lewis also sculpted busts of American presidents, including Ulysses S. Grant and Abraham Lincoln.

Another example of connection with his heritage is seen in The Arrow Maker (1866), a piece that is inspired by his aboriginal roots. The play shows a father teaching his little daughter how to make an arrow.

One of his most famous works was a depiction of the Egyptian queen Cleopatra, titled The Death of Cleopatra. It received critical acclaim when it was exhibited at the Philadelphia Exposition in 1876 and in Chicago two years later. The two-ton sculpture never returned to Italy because Lewis couldn’t afford the exorbitant shipping costs. Therefore, it was stored and rediscovered several decades after his death.

Last years and legacy of Edmonia Lewis

As with his childhood, Edmona Lewis’s last years are shrouded in mystery. It is known that he continued exhibiting his work until the late 1890s, was visited by Frederick Douglass in Rome, and never married or had children. But of its last decade of life, we have hardly any data.

It was speculated that Lewis spent his last years in Rome; However, recently, death documents were discovered indicating that he passed away in London in 1907.

Although despite her status as a woman and black she managed to receive applause for her work in life, it is true that the true recognition would come after her death, at which time, at last, the art world surrendered to her magnificent work. In the late 20th century, Lewis’s life and art have received posthumous praise and his work has been featured in various exhibitions.

Some of his most famous pieces now reside in the permanent collections at the Smithsonian Museum of American Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. We also found some exhibits at the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Howard University Art Gallery. In this way, Edmona Lewis’s legacy can be enjoyed today, applauded, and finally recognized.